This hands-on tutorial demonstrates how to use schemas to organize data and objects you create, a useful technique for storing a collection of learning resources in a single database.

![]() Requirements: You should know how to create a new database and connect to it with psql.

Requirements: You should know how to create a new database and connect to it with psql.

Beginners are encouraged to try these examples (in a new database, of course) and experiment on their own.

Organizing with Schemas

![]() eponymous

eponymous

(of a thing) named after a particular person. “Roseanne’s eponymous hit TV series”

Your Eponymous Schema

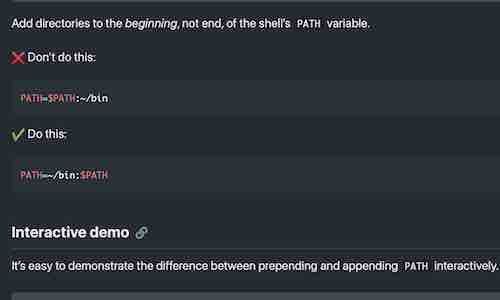

If you create a schema with the same name as your PostgreSQL user account, new objects will be created there instead of the public schema.

For example, create a table in a new database:

> create table t1(i int);

Then create a schema with the same name as the current user:

> select current_user;

current_user

──────────────

stan

> create schema stan;

Create another table:

> create table t2(t text);

List relations:

> \d

List of relations

Schema │ Name │ Type │ Owner

────────┼──────┼───────┼───────

public │ t1 │ table │ stan

stan │ t2 │ table │ stan

![]() Commands starting with

Commands starting with \ are meta commands which are processed by psql. You can learn more about them by entering \?.

The second table was created in the schema we just created. Taking advantage of this default behavior is an easy way to keep new objects organized.

To move the first table we created from public to our renamed schema, use the ALTER TABLE command:

> alter table t1 set schema example1;

When you finish working on a project, rename the schema to something appropriate:

> alter schema stan rename to example1;

You can (should) also add a description:

> comment on schema example1 is 'using schemas: renamed schema';

List schemas with comments by adding “+” to the standard meta command:

> \dn+

List of schemas

Name │ Owner │ Access privileges │ Description

──────────┼──────────┼──────────────────────┼───────────────────────────────

example1 │ stan │ │ using schemas: renamed schema

public │ postgres │ postgres=UC/postgres↵│ standard public schema

│ │ =UC/postgres │

Before beginning a new project, simply create a new eponymous schema. Alternatively, if you don’t want to keep what you were working on, instead of renaming it just use the DROP command to delete your schema before creating a new one.

Understanding the search path

The search_path determines the visibility of schemas:

> show search_path;

search_path

─────────────────

"$user", public

By default, the $user variable is the first schema in the default search_path, which is why new objects are automagically created in your eponymous schema if it exists.

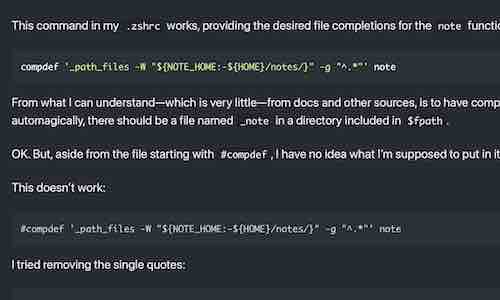

Because our renamed schema (example1) is not in the search_path, its tables aren’t visible:

> \d

Did not find any relations.

However, despite error messages to the contrary, the tables still exist and can be accessed with a qualified name (which includes the schema):

> select * from t1;

ERROR: relation "t1" does not exist

LINE 1: select * from t1;

^

> select * from example1.t1;

i

───

(0 rows)

Changing the search path

Changing the search_path is an easy way to work with a renamed schema without the hassle of using qualified names.

For example, to make the tables in example1 visible:

> set search_path to example1;

> \d

List of relations

Schema │ Name │ Type │ Owner

──────────┼──────┼───────┼───────

example1 │ t1 │ table │ stan

example1 │ t2 │ table │ stan

Don’t worry. The setting is temporary. Feel free to experiment with it. The normal settings will be restored if you reconnect to the database or use the RESET command:

> reset search_path;

Recapping

To summarize, to organize various learning projects in a single database:

- Create an eponymous schema where new objects will be created.

- Rename and add a description to the schema when finished with a project.

- To work with a renamed schema include its name in the search_path.

That’s that not all…

Here’s some other, optional techniques you can use with this workflow.

List tables/views in all schemas

Normally, meta commands like \d only show visible objects. While it’s possible to use wildcard characters (* and ?) to list objects outside of the search path, it’s not always easy.

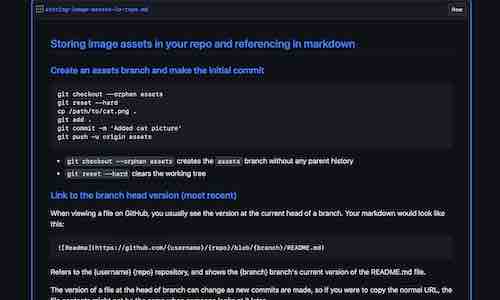

Instead, I use a view to list tables and views from all schemas in a database:

No need for wildcards now:

> table ls;

schema │ relation │ type │ total size │ comment

──────────┼──────────┼───────┼────────────┼──────────────────────────────────

example1 │ t1 │ table │ 0 bytes │ •

example1 │ t2 │ table │ 8192 bytes │ •

public │ ls │ view │ 0 bytes │ list relations in all schemas

![]()

TABLE is a shortcut for SELECT * FROM.

To keep the view visible while working with another schema, add public to the search_path:

> set search_path to example1, public;

Protecting the public from yourself

While it’s not really convenient or necessary for a personal database, we can take this method even further by making it harder (for yourself) to create things in the public schema.

The easiest method is to delete the public schema. There’s nothing wrong with that approach, but you should probably keep it around for testing and experiments while you’re still learning.

A more educational exercise is revoking some or all privileges from the public schema. Such restrictions can be applied to yourself if you’re using an account with limited superpowers:

> set role to dba;

SET

# revoke create on schema public from public;

REVOKE

# reset role;

RESET

> create table test_priv(i int);

ERROR: permission denied for schema public

An easier method is altering the database to remove public from its default search path:

> alter database stan set search_path to "$user";

ALTER DATABASE

(Unlike changes made with the SET command, this change will persist but won’t effect the current session. Reconnect to the database to observe the change.)

With this method, when my eponymous schema doesn’t exist, trying to create a new object returns an error:

> create table path_test(i int);

ERROR: no schema has been selected to create in

LINE 1: create table path_test(i int);

But if I want to create an object in the public schema, I can still use its qualified name:

> create table public.path_test(i int);

Further reading

- PostgreSQL Documentation

- Chapter 5. Data Definition : Schemas - A brief but thorough explanation of schemas and their common use cases, well worth reading.

- Other

- Jonathan Katz: Demystifying Schemas & search_path through Examples - A detailed exploration of schemas, roles, privileges, and security implications.